This post was contributed by Martina Tanga as a summary of Ann Lewis’ process to create “See Her”, a mural bearing witness to the hopes, doubts, and humanity of incarcerated women and offering a reflection on how choices we all make have the power to support their future success.

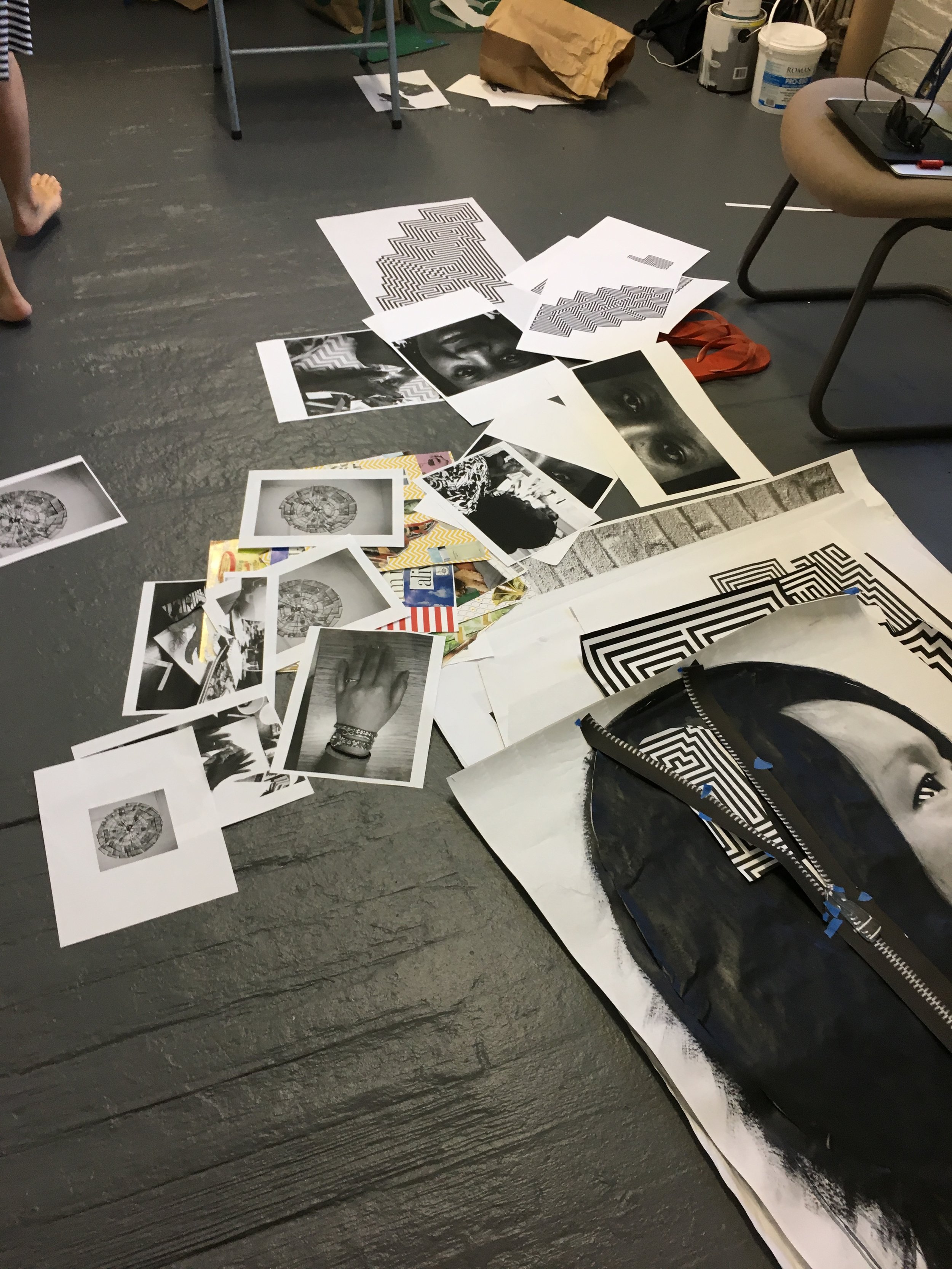

As the warm, summer breeze drifted in from the congested city street outside I sat in a room with eleven women pouring over nature and fashion magazines, cutting out images of interest, and arranging them on a geometrical background. We chatted about why we liked certain pictures—images of strange creatures from the depths of the ocean evoked wonder while an outdated advertisement for a huge laptop computer induced laughter. We snacked on guacamole and chips, drank lemonade or iced tea as we worked. It felt natural; a pleasant afternoon getting to know one another. Except, this experience was unlike anything I had ever done before.

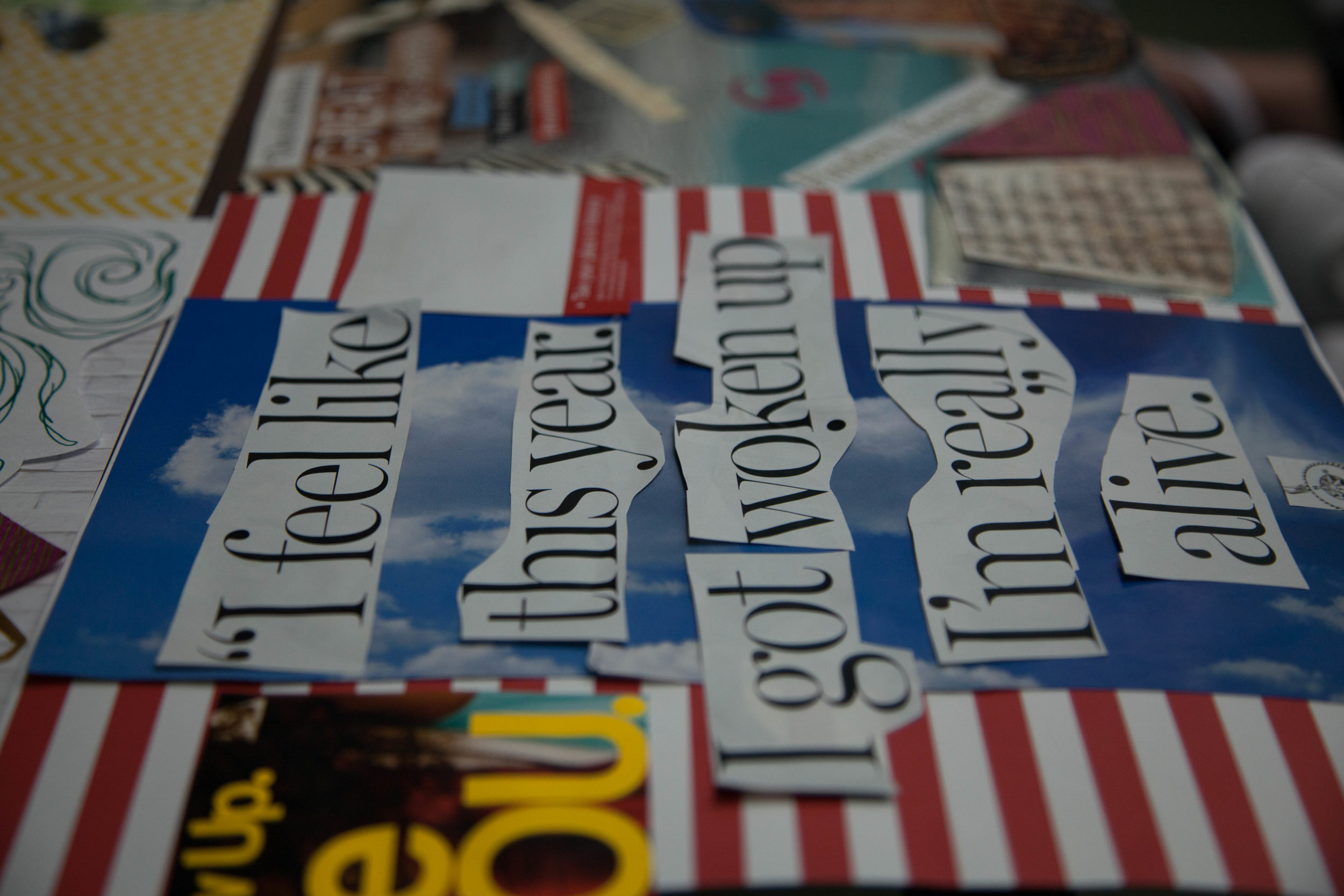

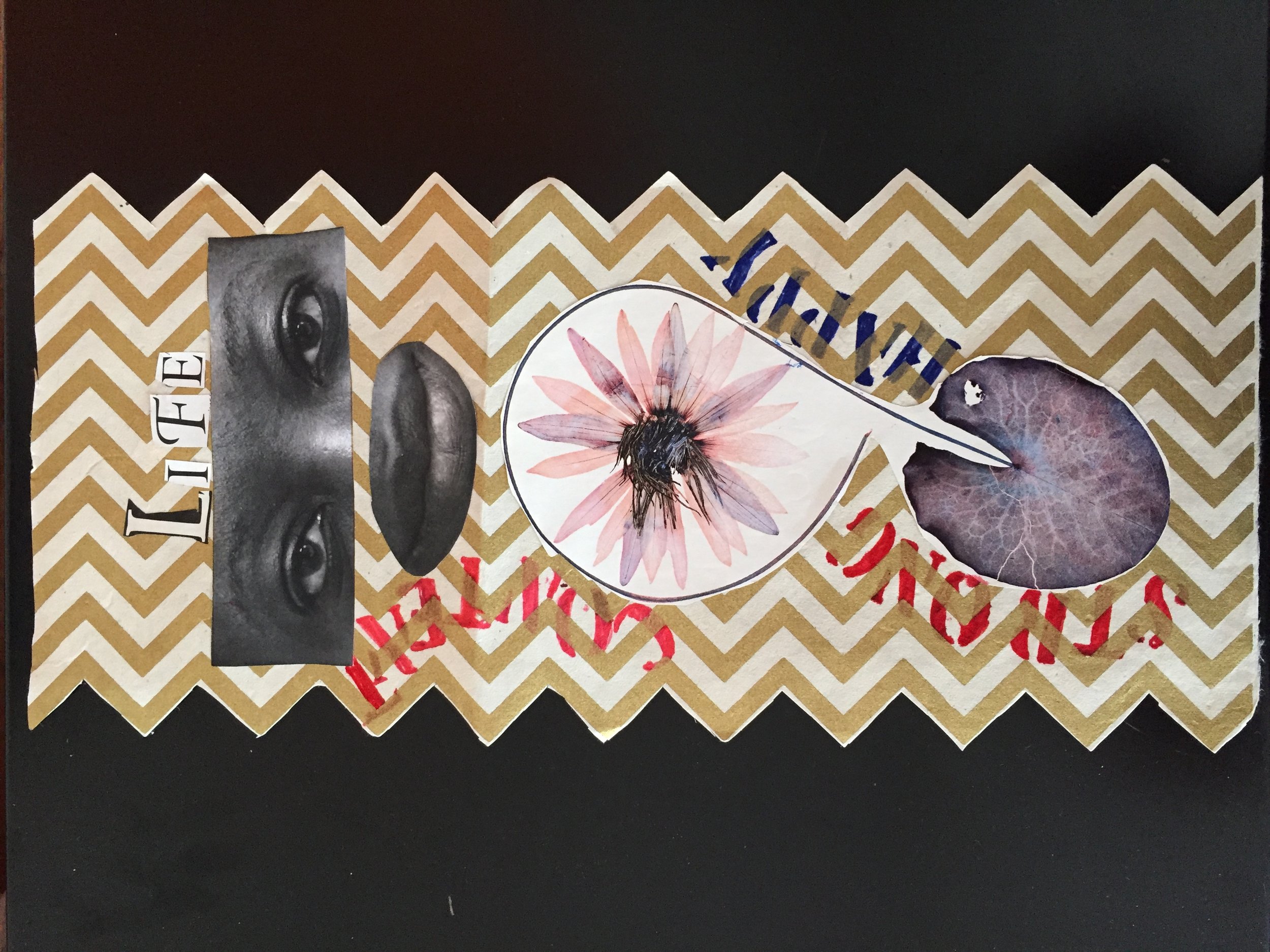

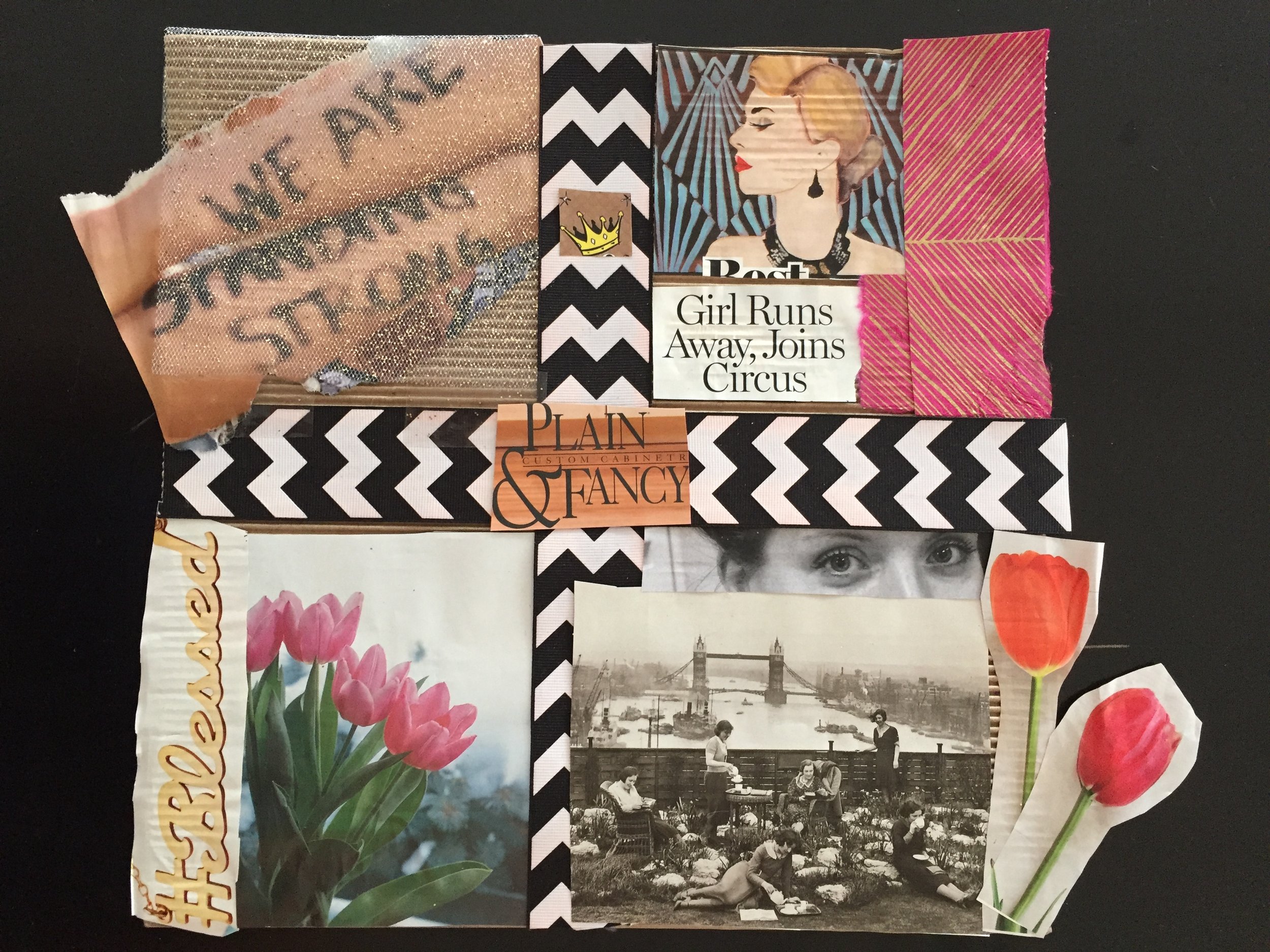

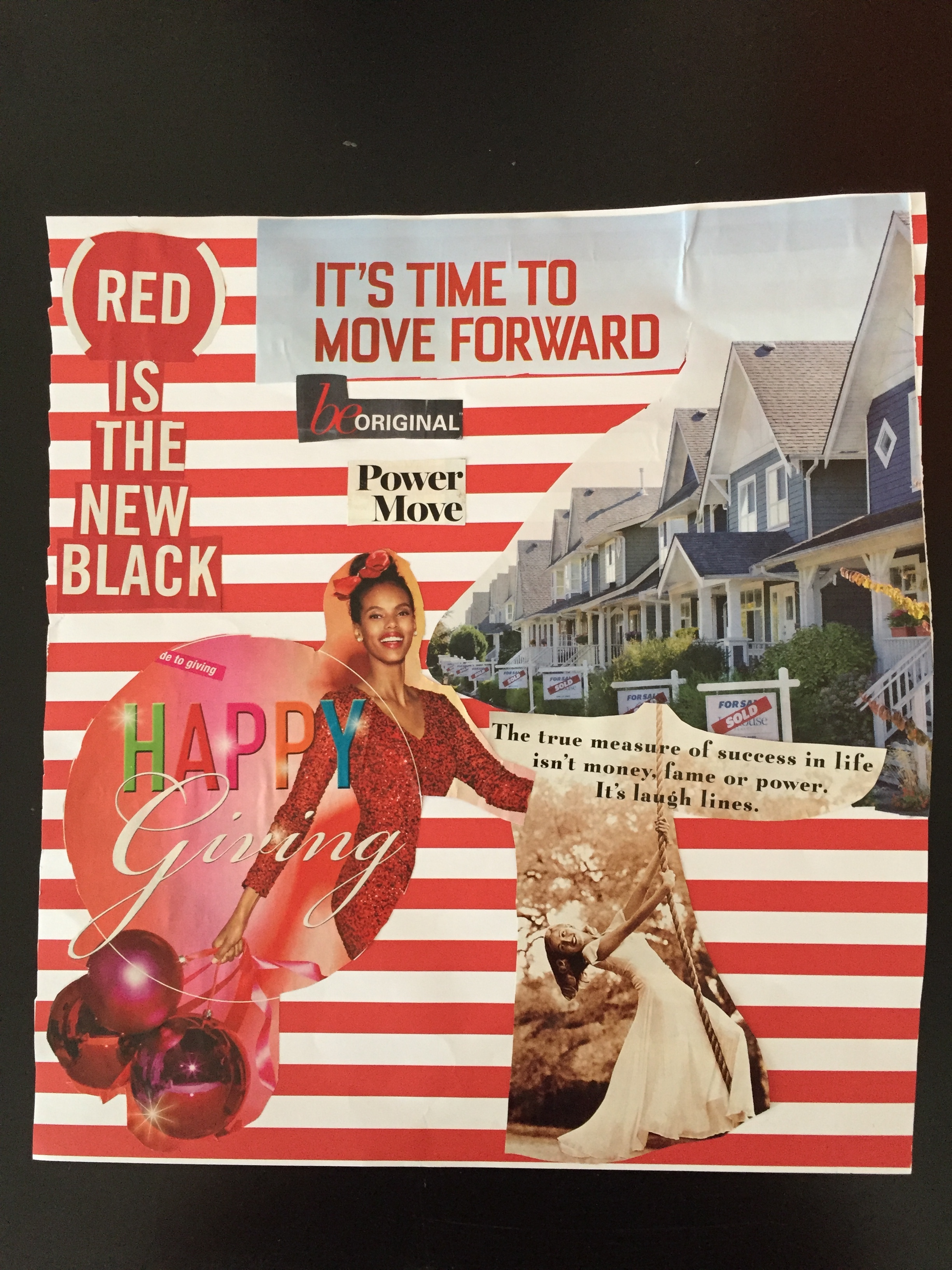

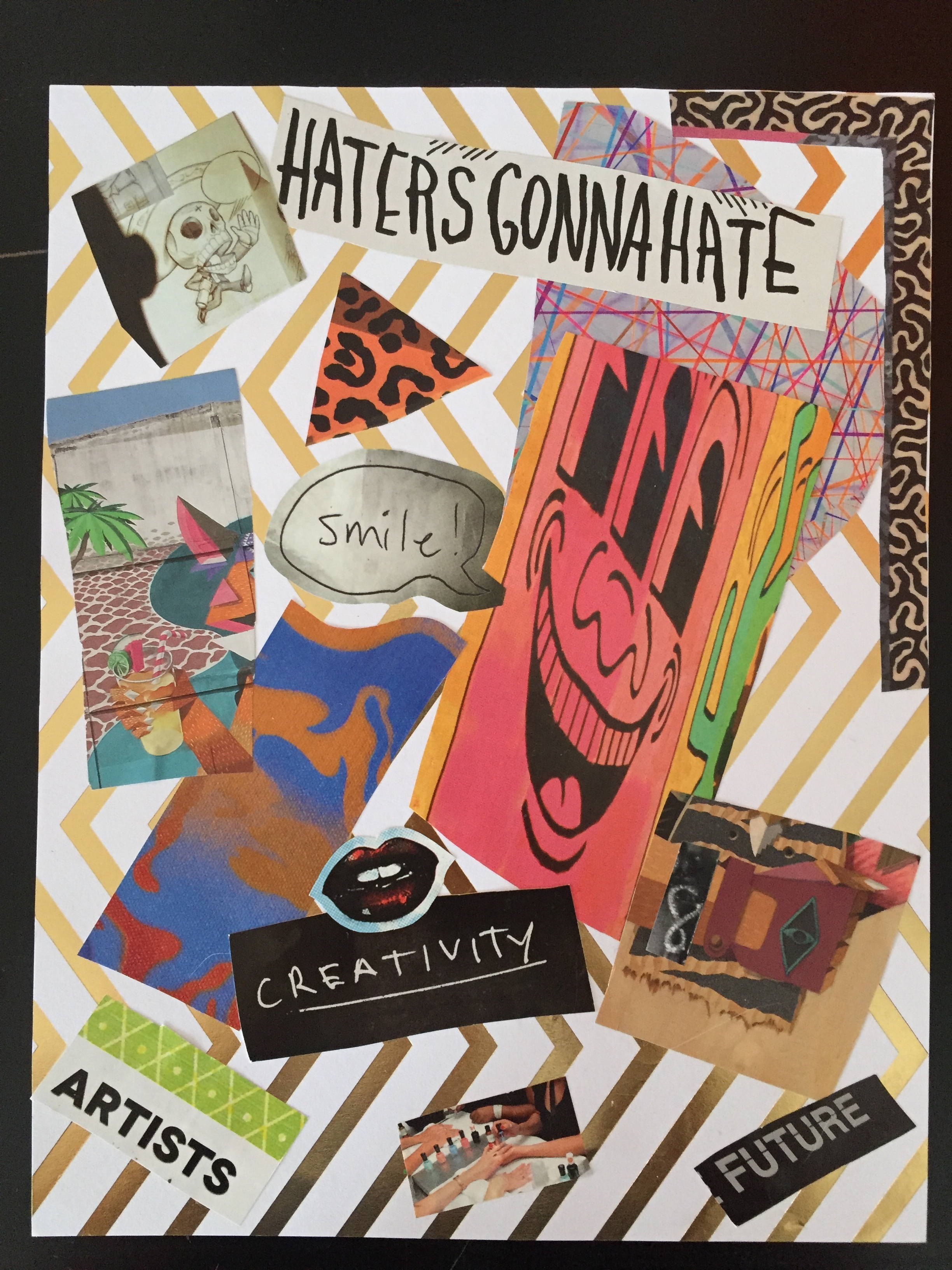

I was facilitating a workshop run by activist artist Ann Lewis for her mural, See Her, commissioned by Now + There. The women I was working with were residents of a local reentry program for incarcerated women, run by Community Resources for Justice. The workshop used the power of creativity to address issues of self-worth, self-care, support, and positive female energy. Spread over two afternoons, Ann, together with educator Chanel Thervil, took us through short stories, conversations, drawing exercises, and lastly, a collage artwork that responded to the prompts: “Who I Am Now” and “Who I Want To Be In The Future.”.

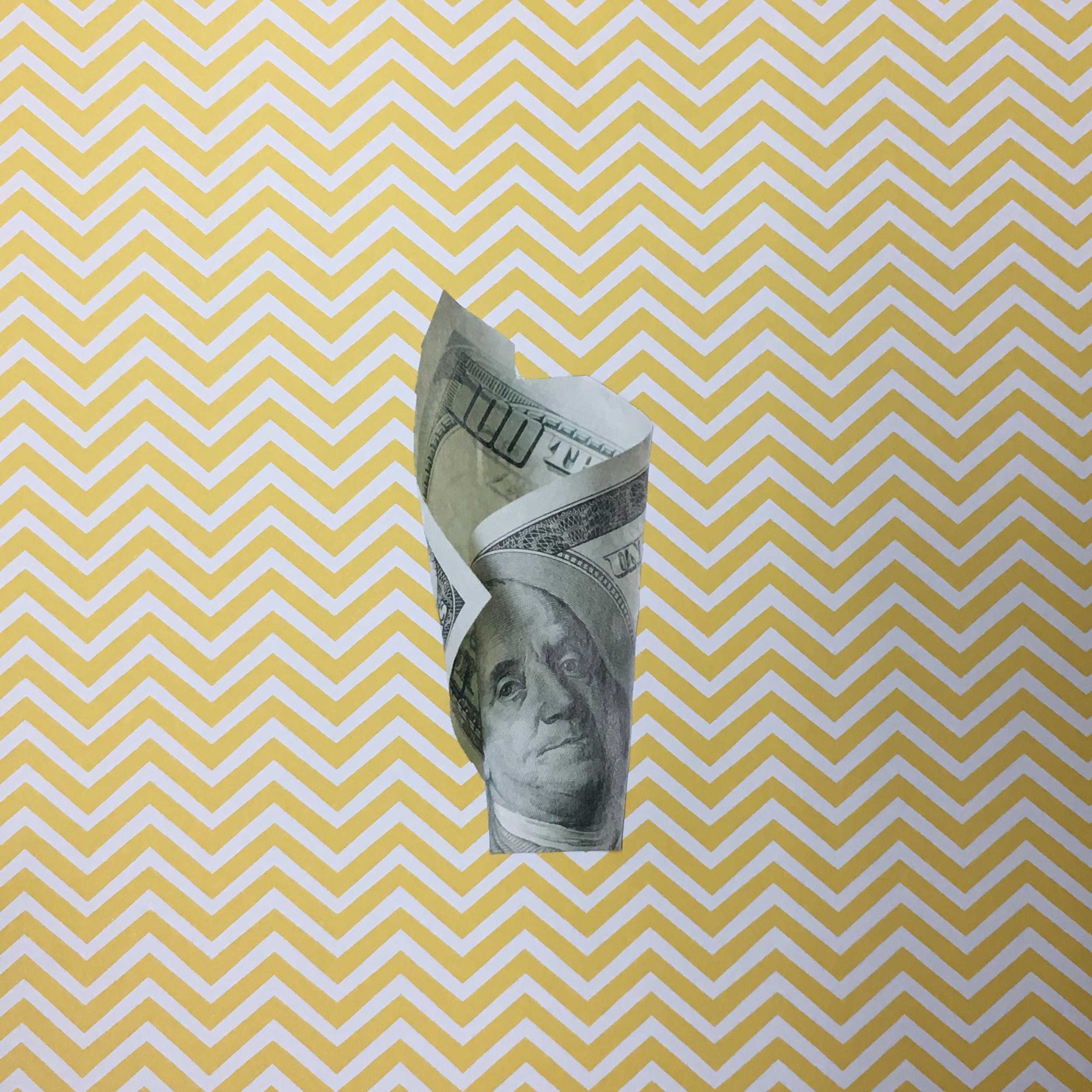

It was clear from our conversations that the women are looking forward to what lies ahead - projecting themselves into a future of happiness, success, and strength. Certain themes emerged that spoke to the struggles these women have faced and will continue to face once they return to their communities. Goals such as being responsible, dependable, self-sufficient, and financially revealed themselves as primary concerns as they neared the completion of their sentences.

What follows is an edited conversation I had with Ann Lewis reflecting on our experiences of the workshop. Note, all the names in this interview have been altered to protect the identities of our collaborators.

Martina: What are your thoughts about the workshop?

Ann: You know, it takes time to get to know people, but over the course of our time together the women relaxed and opened up to sharing their ideas.

The second day I got there sometime before the workshop, just to chat with the women. We were talking about this and that. Just daily life. Human beings being human beings.

During the workshop, it was really cool to learn how they perceive themselves. There was a lot of hopefulness, there was a lot of anticipation. They seemed ready to get on with their lives. I think giving them the opportunity to express themselves in an emotional capacity helped them process things differently than just spending time with a counselor or in a jail cell.

MT: Were the women as you expected them to be? Or did you even have an expectation of what they might be like?

“I think there is a humanity that we lose when we think in terms of “us” and “them”. We create barriers to compassion and a separation of social understanding.”

AL: I did not go in with any expectations. I assumed I’d be working with regular people, because people in prison are regular people. Our society has perpetuated this damaging construct that if you are an inmate then you must be evil all the way through. It’s a very scary stereotype. It was important for me to distance myself from that. Instead, I just thought, “I am going to be working with women today.”

I think there is a humanity that we lose when we think in terms of “us” and “them”. We create barriers to compassion and a separation of social understanding.

One issue that really lay on my mind before I showed up was my privilege. I was aware of the need to be sensitive to their experiences in the way I communicated. I was very conscious of the materials I brought to the workshop and potential triggers. These women don’t come from a position where everything is handed to them. Some did not go on to secondary education. Some grew up without one or both parents. Some may have experienced domestic violence or been victims of crimes themselves. They are not coming from communities where they have been supported. So, I really wanted to accentuate why being supported is so important.

MT: Right, I did not feel like I had the right to judge them. I don’t know all their circumstances.

AL: Yes, but many people DO immediately judge an individual who has gone to prison. We have a box on every job application—have you committed a felony? And we don’t ask for any context if the answer is yes. We don’t ask if that crime was committed in self-defense because your husband was abusing you and you retaliated. We don’t ask if you’ve been trapped in generational poverty and were trying to improve your financial circumstances if you’ve been convicted of fraud or selling drugs. Instead we automatically perceive those who have been part of the criminal justice system as inherently immoral, or dishonest, or malicious. And that’s just not the case.

“We have a box on every job application—have you committed a felony? And we don’t ask for any context if the answer is yes.”

Part of the reason I chose these women was because I want to de-stigmatize incarcerated people and former inmates.

MT: After the workshop I felt really happy to have connected with these women and worked with them—giggled with them, shared ideas. How did you feel when the workshops were over?

AL: I felt proud of the creativity each woman shared with me. And it was fascinating to see different personalities within the group.

For instance, Tilda was so quiet. On the first day she drew a picture of herself falling out of the sky. She said, “There are not enough branches to catch me. My community is not there for me; they do not support me because I went to prison.” So I tried to offer her a different perspective, I said, “Maybe you are not falling, but ascending; maybe you are climbing.” She thought about it at night, and then came back with a totally different idea. And the next day she did a collage with a rock climber and trees. She was a deep thinker and really considered her situation. She’s recognizing her next hurdle and facing it head-on.

And that’s only one story! Once I can get the collages back to the women, they become their vision boards for the future. I definitely learned from them and was inspired by them. I hope I was able to leave them with some tools and ideas to take with them as they make decisions about how to create lives that are fulfilling.

Martina Tanga is an art historian and curator, with an interest in art that engaged with social concerns, the built environment, and audience participation. She received her doctorate from Boston University, and her MA and BA from University College London. Currently, she is the Koch Curatorial Fellow at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.