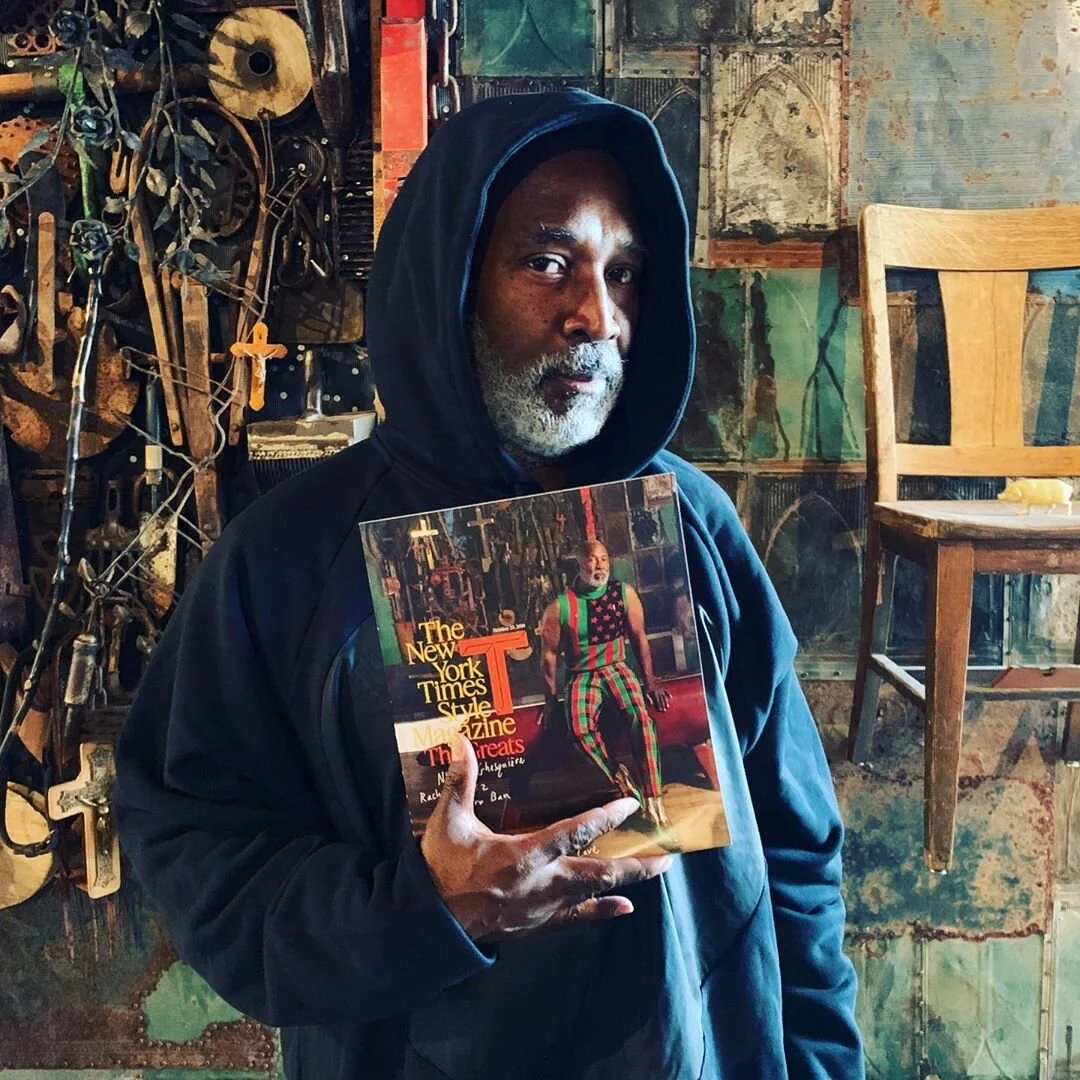

Below is an excerpt from a feature in T Magazine’s 2019 “The Greats” issue. Written by Melanie O’Grady, published on October 18, 2019. The Magazine is available for purchase with a copy of the October 20 edition of the Sunday New York Times.

THE INAUGURATION OF Nick Cave’s Facility, a new multidisciplinary art space on Chicago’s Northwest Side, has the feeling of a family affair. In April, inside the yellow-brick industrial building, the classical vocalist Brenda Wimberly and the keyboardist Justin Dillard give a special performance for a group that includes local friends, curators and educators, as well as Cave’s high school art teacher, Lois Mikrut, who flew in from North Carolina for the event. Outside, stretching across the windows along Milwaukee Avenue, is a 70-foot-long mosaic made of 7,000 circular name tags with a mix of red and white backgrounds, each of them personalized by local schoolchildren and community members. They spell out the message “Love Thy Neighbor.”

The simple declaration of togetherness and shared purpose is a mission statement for the space, a creative incubator as well as Cave’s home and studio, which he shares with his partner, Bob Faust, and his older brother Jack. It’s also a raison d’être for Cave, an uncategorizable talent who has never fit the mold of the artist in his studio. Best known for his Soundsuits — many of which are ornate, full-body costumes designed to rattle and resonate with the movement of the wearer — his work, which combines sculpture, fashion and performance, connects the anxieties and divisions of our time to the intimacies of the body…

Following the phenomenal success of the Soundsuits, Cave’s focus has expanded to the culture that produced them, with shows that more directly implicate viewers and demand civic engagement around issues like gun violence and racial inequality. But increasingly, the art that interests Cave is the art he inspires others to make. With a Dalloway-like genius for bringing people from different walks of life to the table in experiences of shared good will, Cave sees himself as a messenger first and an artist second, which might sound more than a touch pretentious if it weren’t already so clear that these roles have, for some time, been intertwined. In 2015, he trained youth from an L.G.B.T.Q. shelter in Detroit to dance in a Soundsuit performance. The same year, during a six-month residency in Shreveport, La., he coordinated a series of bead-a-thon projects at six social-service agencies, one dedicated to helping people with H.I.V. and AIDS, and enlisted dozens of local artists into creating a vast multimedia production in March of 2016, “As Is.” In June 2018, he transformed New York’s Park Avenue Armory, a former drill hall converted into an enormous performance venue, into a Studio 54-esque disco experience with his piece — part revival, part dance show, part avant-garde ballet — called “The Let Go,” inviting attendees to engage in an unabashedly ecstatic free dance together: a call to arms and catharsis in one. Last summer, with the help of the nonprofit Now & There, a public art curator, he enlisted community groups in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood to collaborate on a vast collage that will be printed on material and wrapped around one of the area’s unoccupied buildings; in September, also in collaboration with Now & There, he led a parade that included local performers from the South End to Upham’s Corner with “Augment,” a puffy riot of deconstructed inflatable lawn ornaments — the Easter bunny, Uncle Sam, Santa’s reindeer — all twisted up in a colossal Frankenstein bouquet of childhood memories. Cave understands that the lost art of creating community, of joining forces to accomplish a task at hand, whether it’s beading a curtain or mending the tattered social fabric, depends upon igniting a kind of dreaming, a gameness, a childlike ability to imagine ideas into being. But it also involves recognizing the disparate histories that divide and bind us. The strength of any group depends on an awareness of its individuals.