On May 7, N+T is going before the Boston Landmarks Commission with our newest collaborator, Boston painter, muralist, and street artist Problak. Read

The Conscious Artist: Identity and Social Responsibility in Boston's Black/Brown Mural Arts

The following post was written and contributed to our blog by Accelerator artist Stephen Hamilton, reflecting on Roxbury's rich tradition of mural arts.

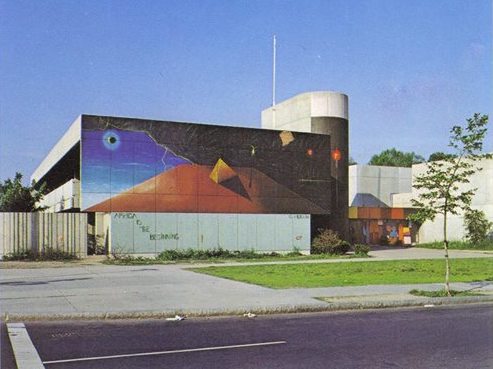

Seeing Africa Is the Beginning emblazoned on the side of the local YMCA is one of my earliest memories. A painting of a single pyramid resting atop a cube floating in space, this mural conjured images of African history as primordial, with its origin so distant in the past as to be beyond human memory.

Africa Is the Beginning by Gary Rickson, photo provided by Anulfo Baez via architects.org.

Even with my limited 5 year old understanding of the world, I knew what Africa was and that I was connected to it by blood and by history. Gary Rickson, the man who painted that mural in 1969-- 17 years before I was born-- taught me part of what that connection meant, and it was that knowledge that made me feel powerful, even before I knew the importance of being empowered.

Africa Is the Beginning wasn’t the only mural in Roxbury charged with this radical energy. During a prolonged era of urban decay offset by, and immediately following, the Civil Rights movement, Black artists such as Rickson used public art as a medium by which to relay core ideas of Pan-Africanism and racial equity. Messages of upward mobility through the development of strong communities unified by a common goal and a common heritage were often made in direct response to the violence, drugs, and poverty that plagued inner city neighborhoods. These issues were the result of generations of institutional racism manifest in over-policing, lack of access to equitable employment, and quality education.

Africa Is the Beginning by Gary Rickson, photo by FORUM Magazine, May 1973 issue via facebook.com.

Art was used to encourage people to take control of their lives and their communities. In Boston, there were many murals, each created in direct response to the needs of some of the city's most disempowered communities. Dana Chandler’s Knowledge Is Power and Sharon Dunns’ Maternity are only a few examples of work created as part of a global artistic movement centered around Black empowerment and pride. Chandler’s piece is a visual embodiment of the importance of education as a means for mental emancipation, a vital tool not only for self-betterment but the betterment of one's neighborhood. The work exists as an artist’s contribution to a larger movement of social justice.

Knowledge Is Power, Stay In School by Dana Chandler, photo by FORUM Magazine, May 1973 issue via facebook.com.

In an era where formalist values set the standard for the mainstream art world, these artists delved deeper into works that were didactic, political, illustrative, and narrative. The iconography and conceptual meaning of their work held the same, if not more, weight as the technical aspects of the paintings in terms of their color, composition, and surface. The mural as a manifestation of mainstream artistic values had long since passed.

However, the audience of these artists were not the elites or tastemakers of the time, but the Black communities in which they lived. Their social commentary lacked the cynicism and pretentiousness of the postmodern agenda. The work was created to make its viewers feel agency, not agency or power over others, but power over themselves, power through self-determination and self-love.

Black Women by Sharon Dunn, photo via facebook.com.

When I was a child in the early 90s, I remember traveling around my native Roxbury with my mother. The elevated train that cut through Roxbury had recently been torn down (it closed the same year that I was born) and Boston was preparing to enter the era of increased construction and “urban renewal.” Rubble and vacant lots dominate much of the memory of my neighborhood at the time.

However, in direct contrast to the constant reminders of urban decay, the murals of Roxbury that created an environment alive with potent symbols of pride and self-determination continued to inspire new generations, especially artists who sought to continue these important narratives.

Younger generations of graffiti artists continued the legacy of this work, infusing it with visual innovations born out of the the Hip-Hop generation. The African Latino Alliance (ALA) and many of their associates have been responsible for creating new temporary murals around the city of Boston, highlighting many of the same issues emphasized in the works of their predecessors. Murals at Peters park such as From The Pyramids to The Projects (which was a direct homage to Askia Ture’s poem of the same name) were in many ways continuation of the themes of revolution and cultural empowerment established during the Black Arts Movement.

From The Pyramids to The Projects: artists Zone, Kwest, Deme5, Marka27, and Problak

Photo By: VQuinonez27 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Even when their works were permitted by the city, these artists stayed true to a radical spirit dedicated to the needs of the communities from which they came. The works were big, bold and beautiful, and they were meant to make their viewers feel the same way. It is this generosity and authenticity that makes their work so powerful and well-respected by their audience.

My credo as an artist has been strongly influenced by the experience of living in communities impacted by this work. My first exposures to public art came from looking at these murals, and from that experience I felt a part of a movement far greater than myself. That was at the core of their message, a rallying cry to marginalized Black and Latino communities in Boston. They tell us that we are beyond the pitfalls of our current circumstance. That in both the past and present we are beautiful and powerful, and with that agency we can take control of our lives and our neighborhoods.

Stephen Hamilton is an artist and arts educator living and working in Boston. His work focuses on the aesthetics, philosophies and key symbols inherent throughout Africa and the Diaspora and creates a dialogue between contemporary Black cultures and the ancient African world. He is currently an artist in our Public Art Accelerator.

![From The Pyramids to The Projects: artists Zone, Kwest, Deme5, Marka27, and Problak Photo By: VQuinonez27 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/548f31e9e4b06e7ab9526659/1521657994548-IYPQPR02BQHBT17RV5CG/%22From+The+Pyramids+to+The+Projects%22+by+the+African+Latino+Alliance)