Leah Triplett-Harrington talks with Liz Glynn and Stephanie Cardon about public space, Boston, and how their projects recontextualize two of our city's most iconic malls. Header photo by Ryan McMahon.

Art as the Mediator for Evolving Communities

They say the only constant thing in life is change, and I’m still trying to decide if I fully agree with that sentiment. More and more, I’ve been leaning towards the theory that change is nothing more than a repetition of patterns if you look hard enough. More than anything, art literally and figuratively continues to remain anchored between the past and present.

Staying in Boston after completing graduate school (partially by choice and partially by circumstance) has made me think a lot about what it means to grow roots. I can easily fall into the category of Boston’s changing demographics, since this coming August will only mark my fifth year residing here. While I can no longer use the magic moniker of “grad student” to gain discounts and access to resources, I’m not sure that I’ve been here long enough qualify as a “Bostonian”. More uncomfortably, I’ve been thinking about whether or not I fall into the category of gentrifier. While I may be well intentioned about wanting to be an active member of the community I reside in, that doesn’t dismiss accountability in how my actions impact said community. As an artist and educator, gaining context is essential to generate next steps. If I aim to grow roots, what pieces of context/history do I need to seek out in order to understand where I am and how my actions will either support or dismantle what was here before I arrived?

Art is my tool of choice when it comes to actions that create a domino effect of positivity. Public art in particular is filled with promise by intrinsically partnering art with placemaking. I witnessed this firsthand through Faces of Mattapan, a public art project I created in partnership with The Boston Public Health Commission and Mattapan’s Violence Intervention and Prevention Program (VIP)’s Our Mattapan Campaign. The Youth Design Team of Mattapan’s VIP, a group of young people ages 14-17, were looking to combat the negative stigma assigned to their neighborhood. During this project we wanted to address both the demeaning nickname “Murderpan” and the reality that these teens and their peers are often perceived as perpetrators of violence. Over the course of a few months I attended their afterschool meetings, got a tour of the neighborhood, and interviewed them about their experiences and I really came to know the neighborhood from their perspective.

A proud member of the VIP Youth and Design Team smiles with Faces of Mattapan by Chanel Thervil.

Photo provided by Chanel Thervil

After completing that process, I created a fifteen-foot painting of Mattapan residents that incorporated phrases illuminating all that they shared. The community unveiling at the Mattapan Library was a joyous occasion where a multi-generational crowd got to celebrate a positive reflection of their community. Many of the youth were pleasantly surprised at the mere attendance of community elders and the interest they showed in hearing about how the young people influenced the creation of the artwork. It was a genuine common ground that supported dialogue about how to keep making their community safer and stronger. That experience served as proof that art is powerful enough to disarm people into forming connections with each other, which is much needed across the city.

Faces of Mattapan by Chanel Thervil on display at the Mattapan Branch of the Boston Public Library.

Photo provided by Chanel Thervil

What I continue to observe and find peculiar about Boston is how it prioritizes preservation of historical elements. Which, by design, thwarts the evolution of aesthetics that help contemporary people connect to the spaces they spend their time in now. The Boston Creates Cultural Plan and The Boston Artist-In-Residence program are examples of the city government’s reckoning with both of those truths. While well intentioned, the structures (or lack there of) beneath the surface of these initiatives tend not to be up to date with removing barriers that keep artists from actually executing this work in real time at such a broad reach. Primary examples include slow disbursement of funds for materials, limited studio space offerings for fabrication, lack of communication and coordination with liaisons or community entities artists are supposed to collaborate with, and shifting timelines that discredit the amount of time artists need to maintain the integrity and quality of what they are asked to produce.

The alternative route that I have seen artists take is to strategically align themselves with organizations/institutions that they have established connections to. Usually this allows them to engage with a more manageable timeline, reasonable disbursement of resources, and immediate interactions with the people within the communities they hope to touch at every level of the creative process.

A poignant example of this can be seen in The Street Memorials Project by artist Cedric Douglas. As a part of his residency at Emerson College, he created a multi-site installation around the campus that focused on memorializing the over 1,000 black people killed by police in the U.S. during the last 5 years. He filled typically ignored crevasses of the campus with gift tags featuring the name, image, age, location, and death year of individuals killed by police. In the time between his guerilla installations, he also conducted community surveys that activated conversations around gun control and safety. One of the more provocative questions people had the opportunity to give verbal or written responses to included: “When is it okay to shoot an unarmed person?”

Street survey in process for the Street Memorials Project by Cedric Douglas.

Photo by Cedric Douglas

Tags pending attachment to roses for gifting to the public for the Street Memorials Project by Cedric Douglas. Photo by Cedric Douglas

The closing of Douglas’ project was marked by a Rose Memorial Service (which was free and open to the public) where attendees paid tribute to those lost and were gifted with a rose. Each rose was marked with the same gift tags that had been part of the installations around campus, yet another way to ensure that the dead are remembered. This is the kind of project that is much needed in Boston, especially considering its history with law enforcement and the policing of communities of color. It’s particularly inspiring to see this led by a person that reflects the community of people targeted by this injustice. The Street Memorials Project poetically challenges us to see victims as individuals rather than statistics, while pointing to the connections between of race, remembrance, safety, and gun control.

A project of that nature is no small feat to complete. But, the stability of installation sites within the confines of a campus, a timeline benchmarked by college semesters and events, and having liaisons that are all working under the same constraints helps to keep things moving toward the common goal: execution and completion of the work. And the reality is this would have been a nightmare to execute on a city-wide level because of the varying historical contexts and contemporary circumstances in the neighborhoods that could potentially be a location for this work. Just thinking of the permit process to make the installations a reality on city property alone summons a headache.

Unfortunately, there’s no overnight solution to how to resolve all of these issues. Art continues to be this remarkable mediator that has the power to address the unique needs that arise from community to community. Despite all that changes, the need for this form of mediation has been unwavering. The key pattern I keep coming back to is the need for support to move ideas from the heart, head, and hands of artists into the streets one project at a time.

Header photo: Here's a peek in the studio while Chanel Thervil paints Faces of Mattapan. Photo by Chanel Thervil

Chanel Thervil is a Haitian American artist and educator obsessed with all things art, history, and community. You can find out more about her work by visiting her website www.chanelthervil.com

The Conscious Artist: Identity and Social Responsibility in Boston's Black/Brown Mural Arts

The following post was written and contributed to our blog by Accelerator artist Stephen Hamilton, reflecting on Roxbury's rich tradition of mural arts.

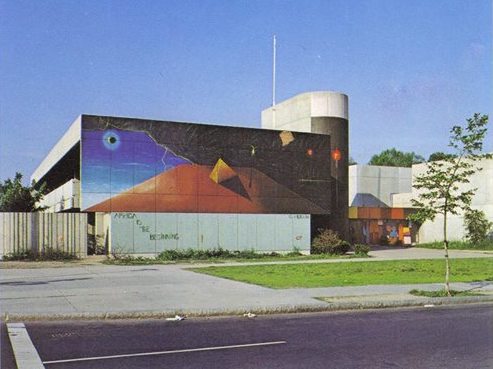

Seeing Africa Is the Beginning emblazoned on the side of the local YMCA is one of my earliest memories. A painting of a single pyramid resting atop a cube floating in space, this mural conjured images of African history as primordial, with its origin so distant in the past as to be beyond human memory.

Africa Is the Beginning by Gary Rickson, photo provided by Anulfo Baez via architects.org.

Even with my limited 5 year old understanding of the world, I knew what Africa was and that I was connected to it by blood and by history. Gary Rickson, the man who painted that mural in 1969-- 17 years before I was born-- taught me part of what that connection meant, and it was that knowledge that made me feel powerful, even before I knew the importance of being empowered.

Africa Is the Beginning wasn’t the only mural in Roxbury charged with this radical energy. During a prolonged era of urban decay offset by, and immediately following, the Civil Rights movement, Black artists such as Rickson used public art as a medium by which to relay core ideas of Pan-Africanism and racial equity. Messages of upward mobility through the development of strong communities unified by a common goal and a common heritage were often made in direct response to the violence, drugs, and poverty that plagued inner city neighborhoods. These issues were the result of generations of institutional racism manifest in over-policing, lack of access to equitable employment, and quality education.

Africa Is the Beginning by Gary Rickson, photo by FORUM Magazine, May 1973 issue via facebook.com.

Art was used to encourage people to take control of their lives and their communities. In Boston, there were many murals, each created in direct response to the needs of some of the city's most disempowered communities. Dana Chandler’s Knowledge Is Power and Sharon Dunns’ Maternity are only a few examples of work created as part of a global artistic movement centered around Black empowerment and pride. Chandler’s piece is a visual embodiment of the importance of education as a means for mental emancipation, a vital tool not only for self-betterment but the betterment of one's neighborhood. The work exists as an artist’s contribution to a larger movement of social justice.

Knowledge Is Power, Stay In School by Dana Chandler, photo by FORUM Magazine, May 1973 issue via facebook.com.

In an era where formalist values set the standard for the mainstream art world, these artists delved deeper into works that were didactic, political, illustrative, and narrative. The iconography and conceptual meaning of their work held the same, if not more, weight as the technical aspects of the paintings in terms of their color, composition, and surface. The mural as a manifestation of mainstream artistic values had long since passed.

However, the audience of these artists were not the elites or tastemakers of the time, but the Black communities in which they lived. Their social commentary lacked the cynicism and pretentiousness of the postmodern agenda. The work was created to make its viewers feel agency, not agency or power over others, but power over themselves, power through self-determination and self-love.

Black Women by Sharon Dunn, photo via facebook.com.

When I was a child in the early 90s, I remember traveling around my native Roxbury with my mother. The elevated train that cut through Roxbury had recently been torn down (it closed the same year that I was born) and Boston was preparing to enter the era of increased construction and “urban renewal.” Rubble and vacant lots dominate much of the memory of my neighborhood at the time.

However, in direct contrast to the constant reminders of urban decay, the murals of Roxbury that created an environment alive with potent symbols of pride and self-determination continued to inspire new generations, especially artists who sought to continue these important narratives.

Younger generations of graffiti artists continued the legacy of this work, infusing it with visual innovations born out of the the Hip-Hop generation. The African Latino Alliance (ALA) and many of their associates have been responsible for creating new temporary murals around the city of Boston, highlighting many of the same issues emphasized in the works of their predecessors. Murals at Peters park such as From The Pyramids to The Projects (which was a direct homage to Askia Ture’s poem of the same name) were in many ways continuation of the themes of revolution and cultural empowerment established during the Black Arts Movement.

From The Pyramids to The Projects: artists Zone, Kwest, Deme5, Marka27, and Problak

Photo By: VQuinonez27 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Even when their works were permitted by the city, these artists stayed true to a radical spirit dedicated to the needs of the communities from which they came. The works were big, bold and beautiful, and they were meant to make their viewers feel the same way. It is this generosity and authenticity that makes their work so powerful and well-respected by their audience.

My credo as an artist has been strongly influenced by the experience of living in communities impacted by this work. My first exposures to public art came from looking at these murals, and from that experience I felt a part of a movement far greater than myself. That was at the core of their message, a rallying cry to marginalized Black and Latino communities in Boston. They tell us that we are beyond the pitfalls of our current circumstance. That in both the past and present we are beautiful and powerful, and with that agency we can take control of our lives and our neighborhoods.

Stephen Hamilton is an artist and arts educator living and working in Boston. His work focuses on the aesthetics, philosophies and key symbols inherent throughout Africa and the Diaspora and creates a dialogue between contemporary Black cultures and the ancient African world. He is currently an artist in our Public Art Accelerator.

Joy and Transgression: Reflections on "Slideshow"

Public Art is About Learning in Public

Making public art has its own unique qualities. The creative process is vulnerable as people can comment and judge before the work is finished. And yet, its very openness at this delicate stage is, in turn, more dynamic in that it constantly sparks interactions with local inhabitants.

Four months after the inaugural celebration of the mural See Her, artist Ann Lewis and Kate Gilbert, to debrief with Martina Tanga about the successes and stumbling blocks of the project.

Hear the stories from "Slideshow" online

Holding a Story - Elisa H. Hamilton on "Slideshow"

An interview with Elisa about Slideshow -- what inspired her, what’s new, and what this piece of “analog” art has to do with a technology and innovation festival (hint -- Instagram wasn’t the original photo sharing platform). Read on to get an inside look at Slideshow and join us for the slide talks, starting Thursday October 12.

Art in Progress: "See Her" by Ann Lewis Bears Witness to the Humanity of Incarcerated Women

Art in Service: Quality

Maggie Cavallo wrestles with the thorny issue of addressing quality in socially engaged art in this guest post, the third in our four-part series Art in Service with Big Red & Shiny and Alter Projects.

![From The Pyramids to The Projects: artists Zone, Kwest, Deme5, Marka27, and Problak Photo By: VQuinonez27 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/548f31e9e4b06e7ab9526659/1521657994548-IYPQPR02BQHBT17RV5CG/%22From+The+Pyramids+to+The+Projects%22+by+the+African+Latino+Alliance)